At the beginning of 1915, the Austrians learned that the Germans had placed electrified wire obstacles around the forts of the fortress Posen. They formed a special commission to visit these fortifications, including Major Jan Gawin-Niesiołowski from the Cracow Engineering Directorate and Captain Eugen Luschinsky from the Befestigungsbaudirektion Vienna. In March 1915, after approving the memorandum of the “commission tasked with investigating high-voltage obstacles in Germany,” the Ministry of War commissioned the Cracow Geniedirektion to develop a detailed design of a high-voltage obstacle and perform systematic experiments on it. Fort group “Mogiła,” located in the sixth “Czyżyny” defensive circuit, was chosen for the trials. Major Niesiołowski directed the operation.

The L. Zieleniewski factory was chosen as a power source for the “Czyżyny” defensive circuit—the output of the factories power plant generator was sufficient to power the electrical barriers in the planned sections. Experimenters decided to construct all power lines from the primary power source to the transformers as overhead lines, made of iron. The length of completed overhead lines amounted to around 10 km. A voltage of 10 kV was transmitted, and the operating voltage in the barrier itself was 1 kV. The obstacle itself was designed to have two rows, with the posts spaced 2 m apart, in front of an existing, ordinary non-electrified wire obstacle.

The shelter for the “Mogiła” transformer station was placed in the bend of the old riverbed of the Vistula, around 600 m to the east of Mogiła Cistercian Monastery. The transformer shelter had a floor area of ca. 15 m2, with daylight plan dimensions of 3 x 5 m—a height of 2.5 m. The shelter’s interior only featured essential equipment: a transformer with a voltage of 10/1.5 kV, a small 10/0.22 kV transformer for lighting, voltage meters, and a telephone for contacting the power plant. The shelter was covered with a single-slope (shed) concrete roof, with a pitch of around 25°. The concrete slab intended to withstand the individual hits of 30.5 cm caliber shells was to have a thickness of 2.0 m. The external walls were hidden in an earthen escarpment, except the backfield facade, which featured an entrance doors. Contemporary on-site measurements indicated that the total length of the flat roof in plan view was ca. 9 m; this would imply that external walls were built of 2 m concrete. The wall from the backfield side (facade wall) was probably less thick—approx. 1.5 m.

The “Mogiła” transformer shelter has survived up to the present days. It lies buried underground, and only a tiny fragment of its concrete gable wall and the ridge of its concrete roof are visible. Despite heavy investment in the area’s linear infrastructure, the shelter has remained untouched. A geodesic benchmark was once affixed into the gable wall, which probably also saved it from destruction. Although the building is small, it is a valuable post-industrial heritage element and an original engineering monument.

Deutsche Zusammenfassung:

Anfang 1915 erfuhren die Österreicher, dass die Deutschen Hindernisse mit elektrisch geladenem Draht um die Forts der Festung Posen aufgestellt hatten. Nach Besuch einer österreichischen Kommission vor Ort beauftragte im März 1915 das k.u.k. Kriegsministerium die Geniedirektion Krakau und die Befestigungsbaudirektion Wien mit der Herstellung zweier Versuchsfelder. In Krakau wurde hierfür die Festungsgruppe „Mogiła“ ausgewählt. Als Energiequelle diente das Kraftwerk der Maschinenfabrik L. Zieleniewski. Von dort wurde der Strom oberirdisch bis zu der Transformator-Station Mogila geführt. Es wurde eine Spannung von 10 kV übertragen, die Betriebsspannung im Drahthindernis selbst betrug 1 kV. Das elektrische Hindernis bestand aus zwei Reihen, vor einem bestehenden, gewöhnlichen, nicht elektrifizierten Drahthindernis.

Das bombensichere Gebäude für das Umspannwerk „Mogiła“ hatte eine Grundfläche von ca. 15 m². Im Innern des Bunkers befanden sich nur die wichtigsten Geräte: ein Transformator mit einer Spannung von 10/1,5 kV, ein kleiner 10/0,22-kV-Transformator für die Beleuchtung, Spannungsmesser und ein Telefon zur Kontaktaufnahme mit dem Kraftwerk. Das Gebäude hatte ein 2 m dickes geneigtes Betondach, welches Einzeltreffern von 30,5-cm-Granaten standhalten sollte.

Die Transformatorenstation liegt heute noch erhalten unter der Erde begraben, und nur winzige Fragmente seiner Betongiebelwand und des First sind sichtbar. Obwohl das Gebäude klein ist, ist es ein wertvolles Zeugnis des postindustriellen Erbes und ein originales Ingenieurdenkmal.

- 1) Zieleniewski factory / Maschinenfabrik 2) Overhead power line / oberirdische Leitungsführung 3) Transformer station / Transformator Mogila 4) Electrified barrage section / Hochspannungshindernis 5) Transformer station / Transformator Dlubnia

- 1) – Interior of the powerstation of the Zieleniewski factory / Kraftswerkshalle der Zieleniewski Maschinenfabrik 2) – power generators / Generatoren 3) – electrical switching station and surge protection of lines / elektrische Schalttafel

- 1) – Location of the transformer station during construction / Transformatorstation während der Bauphase 2) – earth embankment of the floodbank / Hochwasserdamm 3) – route of the power supply cable, the final underground section / Kabelgraben zwischen Transformator und elektrischen Hindernis

- 1) – shelter during concrete works / Transformatorgebäude in der Bauphase 2) – protruding steel rail as a simple grounding conductor / Vorstehender Stahlträger für Erdungszwecke 3) – earth embankment of the floodbank and field railroad used during construction / Hochwasserdamm für Feldeisenbahn genützt

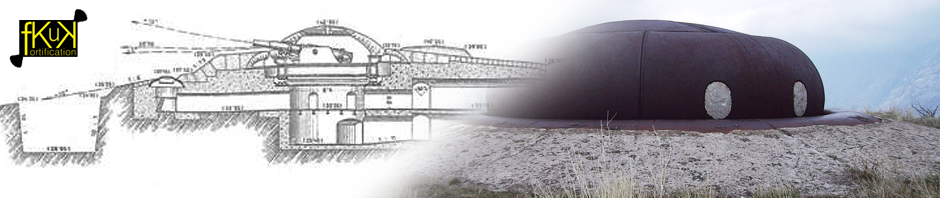

- 1) – steep concrete roof, bombensicher class / bombensichere Betondecke 2) – concrete walls / Betonwände 3) – electrical equipment and transformer / Transformator 4) – entrance / Eingang 5) – protruding steel rail as a simple grounding conductor / vorstehender Stahlträger als Erdung 6) – steel rod for entanglements in wooden insulating foundation / Eisenstab für Drahthindernis mit Holzisolierung

- 1) – part of the concrete gable wall protruding from the embankment / Rest der Giebelwand 2) – a steel beam still protruding from the ceiling as the grounding / Stahlträger der Dachkonstruktion